Difference between revisions of "Khutu"

Forthright (talk | contribs) |

Forthright (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

There are nineteen [[Conduit|Conduits]] appointed by Eluli, and the country is divided into nineteen provinces over which each conduit has some nominal authority. Pragmatically speaking, the conduits live in Onighus and work at the [[Mausoleum]], and have a steward who lives in a major provincial town. The steward is normally a member of the nobility but is, crucially, normally not a member of one of the major noble lineages, and is meant to put a check on the unrestrained behaviour of greedy or power-hungry hengge. <br /> | There are nineteen [[Conduit|Conduits]] appointed by Eluli, and the country is divided into nineteen provinces over which each conduit has some nominal authority. Pragmatically speaking, the conduits live in Onighus and work at the [[Mausoleum]], and have a steward who lives in a major provincial town. The steward is normally a member of the nobility but is, crucially, normally not a member of one of the major noble lineages, and is meant to put a check on the unrestrained behaviour of greedy or power-hungry hengge. <br /> | ||

| − | At the local level, courts, disputes, and taxation are handled by [[Reckoner|reckoners]], as they have been for centuries. Any reckoner can be appointed or removed by Eluli, but practically speaking, these appointments are made by the heads of the major noble lineages in each region or town. Larger communities may have councils of reckoners assigned to adjudicate key matters, while in smaller communities, a single reckoner, or even an itinerant one assigned to multiple communities, adjudicates matters of law, especially concerning disputes between lineages or disputes over taxation. Reckoners' decisions form a body of customary law that may vary from community to community, although communication among them in most regions prevents egregious variation across Khutu.<br /> | + | At the local level, courts, disputes, and taxation are handled by [[Reckoner society|reckoners]], as they have been for centuries. Any reckoner can be appointed or removed by Eluli, but practically speaking, these appointments are made by the heads of the major noble lineages in each region or town. Larger communities may have councils of reckoners assigned to adjudicate key matters, while in smaller communities, a single reckoner, or even an itinerant one assigned to multiple communities, adjudicates matters of law, especially concerning disputes between lineages or disputes over taxation. Reckoners' decisions form a body of customary law that may vary from community to community, although communication among them in most regions prevents egregious variation across Khutu.<br /> |

There is at least animosity, if not outright antipathy, between Khutu and its western neighbour [[Taizi]], over the competing claims of its two emperors, Eluli Ula and [[Zapan Ebesnata]]. Eluli was, of course, the First Emperor of Omba, during the period in which the Empire was truly unified, and although, after his death, other emperors followed, he remained revered that entire time. The Ebesnata emperors of Taizi are descended from Femusa, a young son of the last true Omban Emperor, Ulirega Tirumfegla. But [[Femusa Tirumfegla]], adopted into the Ebesnata after his father's death, was always of questionable parentage and the Ebesnata emperors of Taizi have always been known as Pretenders, and not only in Khutu. In return, Taizians call Eluli the Necrarch, a grave insult.<br /> | There is at least animosity, if not outright antipathy, between Khutu and its western neighbour [[Taizi]], over the competing claims of its two emperors, Eluli Ula and [[Zapan Ebesnata]]. Eluli was, of course, the First Emperor of Omba, during the period in which the Empire was truly unified, and although, after his death, other emperors followed, he remained revered that entire time. The Ebesnata emperors of Taizi are descended from Femusa, a young son of the last true Omban Emperor, Ulirega Tirumfegla. But [[Femusa Tirumfegla]], adopted into the Ebesnata after his father's death, was always of questionable parentage and the Ebesnata emperors of Taizi have always been known as Pretenders, and not only in Khutu. In return, Taizians call Eluli the Necrarch, a grave insult.<br /> | ||

Revision as of 12:11, 25 July 2023

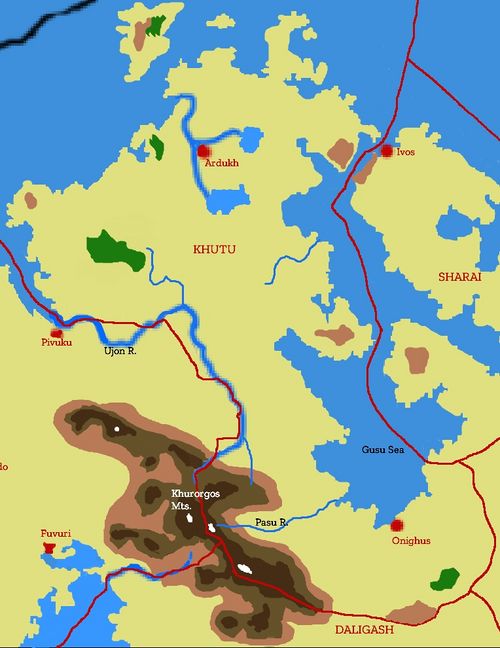

Khutu, also known poetically as The Grey Rivers, formally as the Omban Empire, and derogatorily as the Necrarchy, is a relatively small, craggy monarchy (of sorts) that relies heavily on maritime products, mining, and grain agriculture. Located along the coast nestled between Sharai and Taizi, and with its interior bordered by the great Gusu Sea, it is a land oriented to the sea economically. It is one of the older and more traditional former provinces of the Omban Empire, governed by a council of aristocratic priests of the Voice of the Dead. Its principal claim to fame is that the body and spirit of First Emperor, Eluli Ula, reside in the capital of Onighus, where his spirit is regularly consulted on any decisions of national import. In effect, he is the Emperor and decisions are made in his name. During the time of the Empire, Eluli was honoured but power lay in the hands of his descendants; in Khutu, since the empire fell, he has acquired power, tempered by the fact that he cannot move or act on his own. The Voice is much more powerful than the Hand here, and Khutu is home not only to the Emperor but also numerous other important saints. Nineteen important aristocratic priests are chosen, largely on the basis of birth rather than merit, as Conduits for the will of the sainted emperor, and exercise power through controlling access to the bodies of the revered. Pilgrimages to the Mausoleum in Onighus are a major source of revenue, as individuals from throughout the former Empire come to visit the bodies of their noble ancestors. Khutu maintains a studied neutrality in most political affairs; most other nations are reluctant to attack it directly out of respect for Eluli, and it has become very conservative and inward-looking. The name Khutu may derive from Old Omban khuat, 'west', a reflection of the period during which Khutu would have been at or toward the west of the Omban region. Alternately, it may derive from an early hypothetical OO *hha tua(-nne) 'grey rivers'. Khutu is sometimes still known colloquially as the Grey Rivers in poetry and myth.

Geography

Geographically, Khutu is often conceptualized as having two centers - the northlands, centered around the city of Ardukh, and the south, centered around the capital of Onighus, which are connected by a narrow strip of land between the Ujon River on the west and the Gusu Sea on the east. The total population of the country is perhaps 1,100,000 or so. The north is dominated by the coastal fishing and whaling industries, and mercantile trade from Omba, Sharai, and Basai especially. The northern capital Ardukh, a city of over 30,000, is located at the confluence of the Isikh and Aghong rivers, and is heavily agricultural in the low floodplains of the region. In the far north, there are a number of coastal small islands that are administered by Khutu. The largest and most important, Taigeltur, is a major whaling center and has strong ties to the Luetkan islands, to the north.

The southern part of the country is dominated by the capital city of Onighus, located at the southern tip of the Gusu Sea. Onighus, just over 40,000 population, has been the seat of Eluli Ula since before the end of the Omban Empire. Onighus is located just a few days' ride west of the ancient capital of Omba herself, and still has strong trade and social connections with Omba. The southwestern part of Khutu is upland hills leading to mountains, the mighty and ancient Khurorgos Mountains, with the great peak Momichas in the far southwest looking far over the countryside. Here are some of the parts of the country most untouched by recent history, in the deep vales and crags of the uplands.

Politics

The leader of Khutu is the First Emperor Eluli Ula, a revered saint. He resides in the capital of Onighus, where he is regularly consulted on any decisions of national import. In effect, he is the Emperor and decisions are made in his name, although the degree to which he is directly involved in the affairs of state varies. During the time of the Empire, Eluli was honoured but power lay in the hands of his descendants; in Khutu, since the empire fell, he has acquired power, tempered only by the fact that he cannot move or act on his own. Khutu is a monarchy in the sense that it is a single ruler, and Eluli is always known by the title of Emperor, because, through him, the country still claims titular governance over the entirety of the old Omban state. It is considered transgressive or insulting to refer to Khutu as a kingdom, for, as its leadership will remind you, it has no king.

The Voice is much more powerful than the Hand here in politics, and Khutu is home not only to the Emperor but also numerous other important saints. Nineteen important aristocratic priests are chosen, largely on the basis of birth rather than merit, as Conduits for the will of the sainted emperor. These are lifetime appointments, made by Eluli himself in conjunction with the other Conduits. They exercise power through controlling access to the bodies of the revered, access to the Emperor himself, and to the incredible repositories of knowledge held by the Voice. They are responsible for matters of state, military, diplomacy, and matters that affect the entire country.

There are nineteen Conduits appointed by Eluli, and the country is divided into nineteen provinces over which each conduit has some nominal authority. Pragmatically speaking, the conduits live in Onighus and work at the Mausoleum, and have a steward who lives in a major provincial town. The steward is normally a member of the nobility but is, crucially, normally not a member of one of the major noble lineages, and is meant to put a check on the unrestrained behaviour of greedy or power-hungry hengge.

At the local level, courts, disputes, and taxation are handled by reckoners, as they have been for centuries. Any reckoner can be appointed or removed by Eluli, but practically speaking, these appointments are made by the heads of the major noble lineages in each region or town. Larger communities may have councils of reckoners assigned to adjudicate key matters, while in smaller communities, a single reckoner, or even an itinerant one assigned to multiple communities, adjudicates matters of law, especially concerning disputes between lineages or disputes over taxation. Reckoners' decisions form a body of customary law that may vary from community to community, although communication among them in most regions prevents egregious variation across Khutu.

There is at least animosity, if not outright antipathy, between Khutu and its western neighbour Taizi, over the competing claims of its two emperors, Eluli Ula and Zapan Ebesnata. Eluli was, of course, the First Emperor of Omba, during the period in which the Empire was truly unified, and although, after his death, other emperors followed, he remained revered that entire time. The Ebesnata emperors of Taizi are descended from Femusa, a young son of the last true Omban Emperor, Ulirega Tirumfegla. But Femusa Tirumfegla, adopted into the Ebesnata after his father's death, was always of questionable parentage and the Ebesnata emperors of Taizi have always been known as Pretenders, and not only in Khutu. In return, Taizians call Eluli the Necrarch, a grave insult.

Unlike areas of the former Empire that have been heavily ravaged by border disputes and wars, Khutu has remained relatively peaceable over the last 300 years, since the end of the Khutu-Taizian Wars. The western border of Khutu has been well-established as following, for the most part, the Ujon River which flows northward from its source in the Khurorgos Mountains to the sea. Within the mountains themselves, the borders with Taizi, and Daligash are much less clear. These uplands are sparsely inhabited by herders and country folk whose lives are far removed from the concerns of the coastal aristocrats. The southern and eastern lowland borders of Khutu with Daligash and Omba are longstanding and traditional, following noble lineage landholdings now centuries old.

Khutuan neutrality was tested most recently in the Bone War of 727-730 I.E. in which Khutu's eastern neighbour, Omba, fragmented as the northern peninsulas seceded and became the now-independent Kingdom of Sharai. The Senate of Omba appealed to Khutu at that time to break its neutrality and support the Imperial homeland against the uprising. However, Sharai's powerful navy, which held sway over the arms of the Gusu Sea, dissuaded Eluli Ula from action.

Social Organization

To a larger degree than in many of the other Omban successor states, Khutu's lineage structure reflects old Omban norms. Especially in comparison to its highly republican, urban neighbour to the south, Daligash, Khutuan ideas about the mufanne (ranks) are held firmly.

At the top are the nobility (sajari), which comprises less than 5% of the population. Khutuan nobles owe their allegiance only to the Emperor and his Conduits, but exercise a high degree of liberty over local affairs in their own territories. They often are responsible for selecting (sometimes from within their own ranks) powerful reckoners and as such have a great deal of control over law and property in large parts of rural Khutu. The cities of Onighus and Ardukh are somewhat exceptional in this regard, but even there, the expectation of noble privilege is maintained.

Because of the role of Eluli Ula in social life, saints occupy a greater role in Khutu than elsewhere, although inevitably they are still the tiniest minority (perhaps a hundred through the whole country). Saints themselves, other than Eluli, do not directly have a role in political affairs. However, many of them have powerful saintly lineages (ulaji), which stand somewhat outside the noble-common-country hierarchy of ranks, especially within Khutu, as they mark the establishment of a new lineage of that saint's real or fictive kin. Nonetheless, the nobility is firmly in agreement that saintly lineages, though worthy of esteem, are clearly below the nobility in status, and marriages between saintly and noble lineages are discouraged in many places.

Khutuan custom also retains a much stronger memory than other successor states of the distinction between common lineages (galti) and country lineages (tenuf). Common lineages are - in principle - lineages descended from Omban citizenry of the Imperial period, while country lineages consist of descendants of those who were never Omban citizens, but were members of hill tribes or other marginal people. Common lineages include various craft lineages (okhi) focused on particular trades or products, with no distinction made between these, and intermarriage between common and craft lineages is perfectly ordinary. Common lineages include a wide variety of levels of wealth and social status, but do tend to be landholding at the lineage level. A completely landless common lineage runs the risk of disintegrating particularly as its members choose other kin groups to affiliate with.

Although the concept of citizenship itself did not long outlast the Empire, there is still a social recognition, independent of wealth, that country folk are in some ways still outsiders, and intermarriage between country and common lineages is much less common than in other countries. In rural area, country folk such as the Ravre may even have their own settlements, although any community of sufficient size will have a mix of common and country lineages. Even though all speak the Khutuan dialect of Ombesh, and all follow the Corps, there is still a distinction between the two, preserved in local memory and reckoners' ledgers. Marriage with country folk is frowned upon (though not prohibited) and, in particular, land transfer from common lineages to country lineages as part of bridewealth is seen as a violation of social norms.

Corpseborn are relatively common in Khutu and are treated with a comparable level of disgust and pollution as they would be in Taizi, Sharai, or Omba, but considerably worse than in Daligash. Urban corpseborn are generally relegated to walled ghettos and bound by strong sumptuary laws, while in rural areas, they have their own separate communities.

Religion

As with the other Omban successor states, the Corps is the main and only official religion of Khutu. Because of the importance of Eluli Ula the emperor-saint, the Voice of the Dead, in particular, occupies an extremely prestigious role in the politics and culture of the country, especially in southern Khutu. Noble lineages regularly send their sons and daughters into the priesthood as a means to exercise greater political authority.

A large number of saints make their homes in Khutu, giving it the moniker Ulanai 'sainted, sainted land'. The protection and patronage of Eluli and of the powerful Voice of the Dead have led several saints to locate themselves here, even if they are not originally from Khutu. Because saints are of different ages, come from various social classes, and have different powers and interests, the cults surrounding each saint may exhibit minor theological variances from the central Corps beliefs, but normally, these are held in check by Eluli Ula and the Conduits, who hold the vast majority of both secular and theological power in Khutu. When heresies do emerge surrounding particular saints, this can be a cause for considerable strife.

There are, at least in the official count, no Hulti in Khutu. A series of purges over the past several centuries have all but eliminated the Old Folk within its bounds, because the Hulti faith rejects revenants, bubun, and saints as aberrations. Nevertheless, accusations of Hulti or crypto-Hulti faith are sometimes heard in rural communities, levelled against individuals or families perceived as deviant or undesirable.

Culture

Khutu, uniquely among the Omban successor states, uses the Negili Reckoning, the older, more complex calendar that by imperial decree was replaced by the Fair Cycle in 215 IE and which, by the time the Empire ended in 338 IE, was rarely employed elsewhere. One of Eluli Ula's first acts was to restore the Negili calendar, named after a village, now ruined, where it was developed. Unlike the aptly-named Fair Cycle, the Negili Reckoning has months of greatly differing lengths, and there is a five-day high midsummer festival, Romokh, during which all work ceases. Even progressive Khutuans who may follow the Fair Cycle for business reasons are very serious about Romokh festivities, which involve great displays of wealth and artistic and athletic prowess.

A widely-known Khutuan proverb is "When doubt exists, look down." This refers, firstly, to the notion of the past metaphorically existing beneath the earth. It is not a narrowly conservative place, but having an ageless, timeless saint-emperor has surely influenced the ethos of the elite, at least, towards a distrust of radical social change.